|

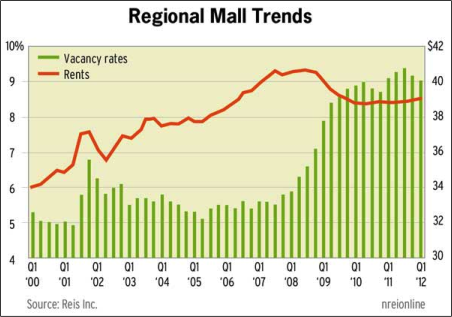

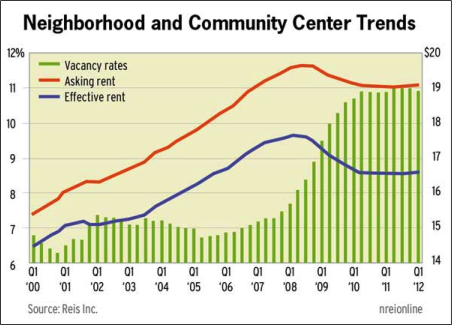

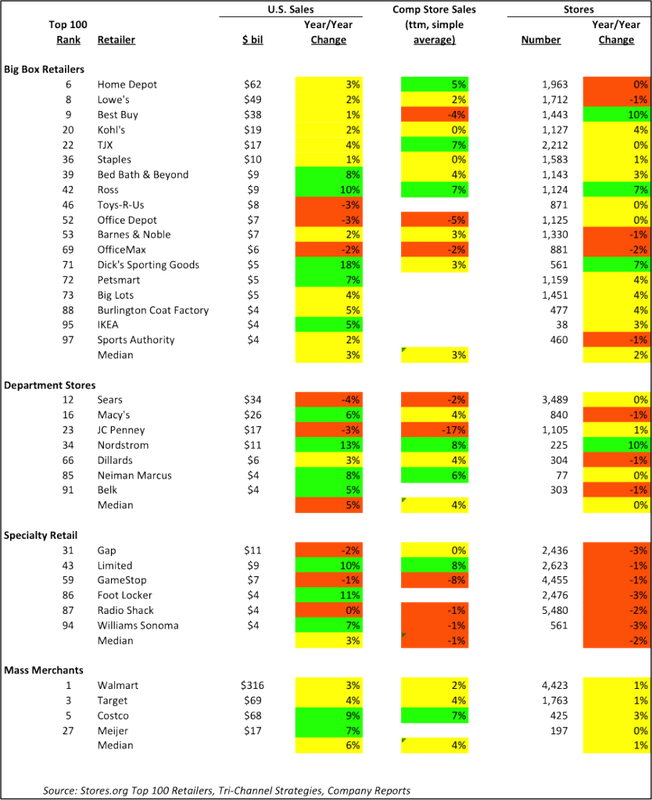

"I don't think we're overbuilt, I think we're under-demolished" -- Daniel Hurwitz, CEO of DDR, a commercial property owner and manager, talking about malls. I came across a blog post from Jeff Jordan, a Partner with venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. The gist of the post is in its title: "Why Malls Are Getting Mauled." Why would a venture capitalist be interested in malls? Because they fund online retailers (Jeff sits on the board of Fab.com and was previously a senior executive with eBay). Online retailers are the antithesis of malls. So even though Jeff is clearly rooting for online retailers in the online retailers vs. malls battle (if that can be billed as an actual battle), he presents some very compelling data. The data is interesting enough that Jeff expanded on his blog post in an article for The Atlantic Cites, which can be read here. There are three self-explanatory figures from the article that are worth showing here: To summarize the above three figures, malls are hurting. Rents are flat and vacancies are increasing. And it's not like it's going to get better soon, seeing as many of the retailers that inhabit malls are hurting. The growth prospects don't look good. Hence the opening quote from Daniel Hurwitz. Unless the weak malls and retailers are culled from the herd, traditional brick-and-mortor retail properties will suffer. If you are a contractor that specializes in mall construction or sees a healthy percentage of your billings come from mall or brick-and-mortor retailers, this is troubling news. The pace of construction in that market is likely to decrease further, that is unless growing retail trends in the United State reverse course. If you are a contractor that has pursued work from retailers like Mervyn's, Circuit City or Borders, you already know this.

On the flip side, online retailers continue to grab market share from brick-and-mortor retailers. So while the market is closing the door on physical retail space construction, it's opening one for all things associated with online commerce. (*Note: I'm not predicting the death of malls and other physical retail stores. They will survive. There will just be fewer of them as time goes on if current trends hold. With more sales going online and lower rents from physical stores, the economics will call for fewer physical retail stores, and hence, less investment in them. But it won't go to zero anytime soon. Plus, with vacancies going up, and spaces changing hands, there may be increasing opportunities for tenant improvements. I just wanted to make that clear) So what does working in online commerce look like for commercial builders? Well, instead of clients like Sears, Macy's or Home Depot, your clients will be Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, etc. Instead of expansive retail spaces split up for individual stores and large tilt-up buildings for big box retailers, projects will be office buildings filled with cubicles, high-tech warehouses with miles of automated conveyor belts for fulfilling orders, and server farms that hold gobs of data. Google has an estimated 1 million servers split over 40 locations, and they're building more. There will be much fewer marble entrances, water fountains, glass curtain walls and other fancy architectural finishes and much more electrical and HVAC components (server farms, for example, suck electricity and require a lot of cooling). I will be coming back to this topic in the future because it's a deep vein of conversation. Some topics I hope to cover soon include:

But for now, let's just acknowledge that the competitive landscape of retailing is shifting, so general building contractors and their trade partners must be prepared to shift with it.

1 Comment

I thought I was done talking about real estate for 2012. But a wave of good news has been landing so I wanted to pass it along. Just to reiterate, my primary interest in the single family housing market is that it is an indicator of the health of the overall construction market and the economy in general. Very few of my students and industry friends are in the single family construction industry, but good health in that market generally points to good news in the market for other (bigger and more complicated) construction projects. I'll separate the news by date. See if you can detect the trend: December 20, 2012:

December 26, 2012

December 27, 2012

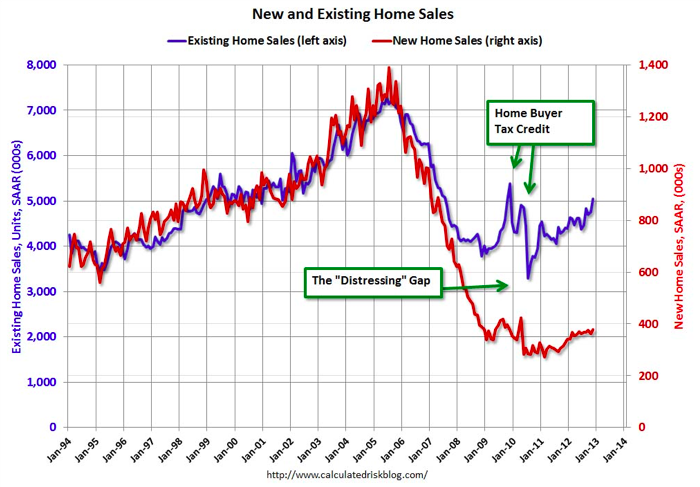

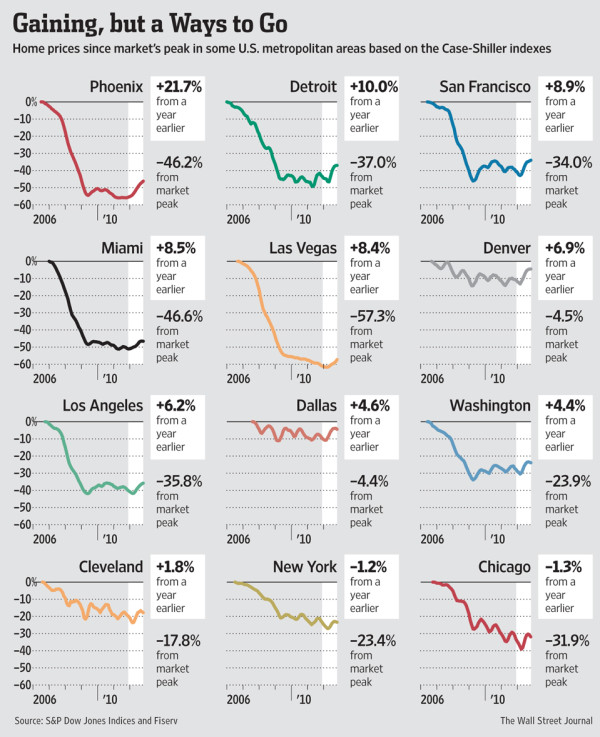

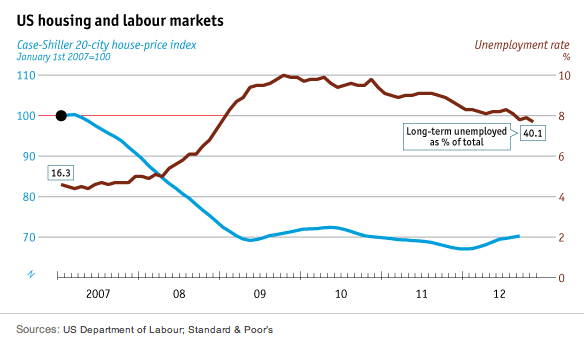

Existing home sales outpaced new home sales during the recession because many of the existing home sales were of distressed homes at bargain basement prices. New homes could not compete with the lower priced existing homes, so sales of new homes fell. As the number of distressed properties decreases, new home sales should increase, closing the "Distressing " Gap. This is good news for general contractors, because as new homes are built, so are adjunct buildings (schools, firehouses, retail, etc.). Other Miscellaneous Data: Looking at the two figures above, the Case-Shiller price index is getting better in most places in the U.S., particularly the places that were hit hardest during the downturn (Phoenix, Las Vegas, Miami, I'm looking at you). However, we are still a long way from the pre-recession peaks. The second figure I threw in this post because I found it interesting. It seems, at least from 2007 on, that the Case-Shiller index and unemployment are inversely proportional. So, if unemployment decreases, hopefully Case-Shiller will increase (sort of a master-of-the-obvious observation). OK, so what does all the data above show? It seems to indicate that the housing market is getting better. This would traditionally indicate that the economy is getting better and that construction activity should be increasing (institutional and commercial construction tend to lag housing). This should be good news for general contractors. Except... What's the bad news? Sorry, but we're not completely in the clear. In fact, there is a considerable amount of uncertainty in the market. It stems partly from:

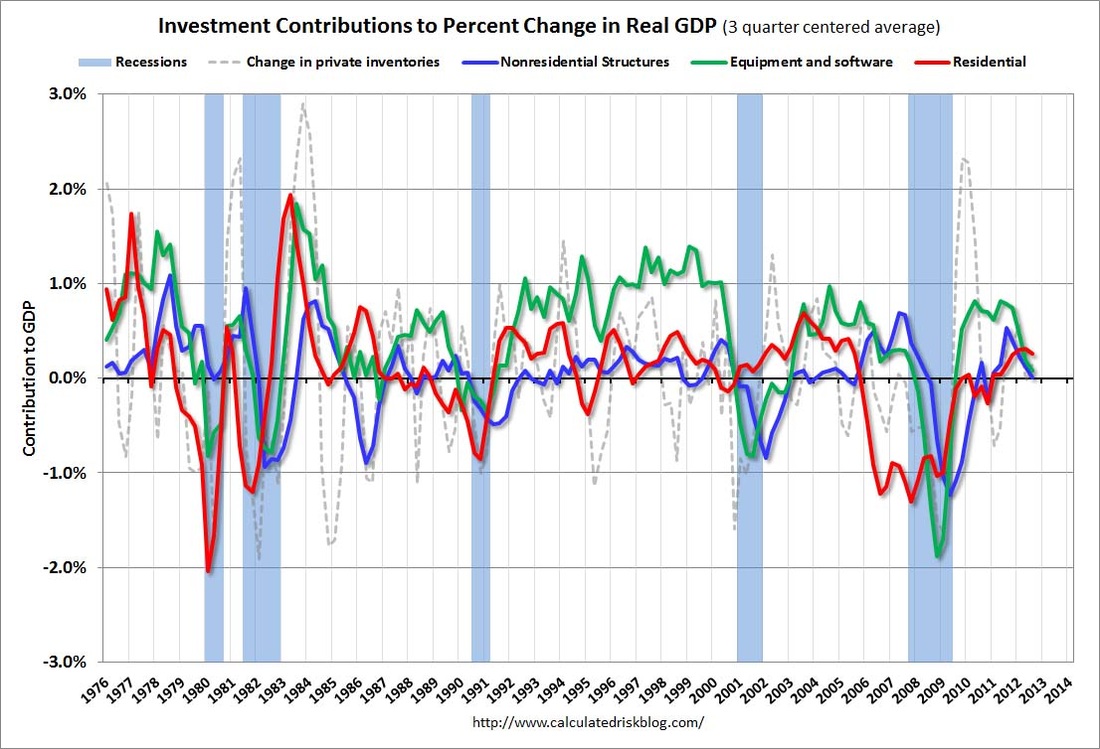

So the housing market looks like it's improving and the data supports that it is. But lurking in the background is a fragile economy (and we haven't even mentioned the fiscal cliff or any other external factors that could upset the market). If this housing market improvement has legs, then that's good news for the construction industry (and the economy as a whole). If it doesn't, well, we're stuck in the same slow construction market we're currently slogging through. I guess like many things in life, we'll just have to wait and see. But wait there's more! I want to leave you with one last figure, again courtesy of Bill McBride: The above figure shows the contribution to GDP from residential investment (which includes home building), equipment & software, nonresidential structures (what general contractors should be interested in), and "change in private inventories." These are the four categories of private investment. As discussed above (and in other posts), residential real estate tends to be a leading indicator of the economy and nonresidential structure investment is a lagging indicator (equipment and software is neutral). But this didn't happen in this recovery--housing has lagged. This was due to the inventory that grew so large during the recession (but has been slowly been whittling down). Perhaps this recent (2012) strengthening in the housing market is the indicator that the economy is getting stronger, all other signs weakness notwithstanding. If so, then expect the blue line in the figure above to reverse course, a trend that would be positive for general contractors. For Bill's full post on this (which is a very worthy read), click here.

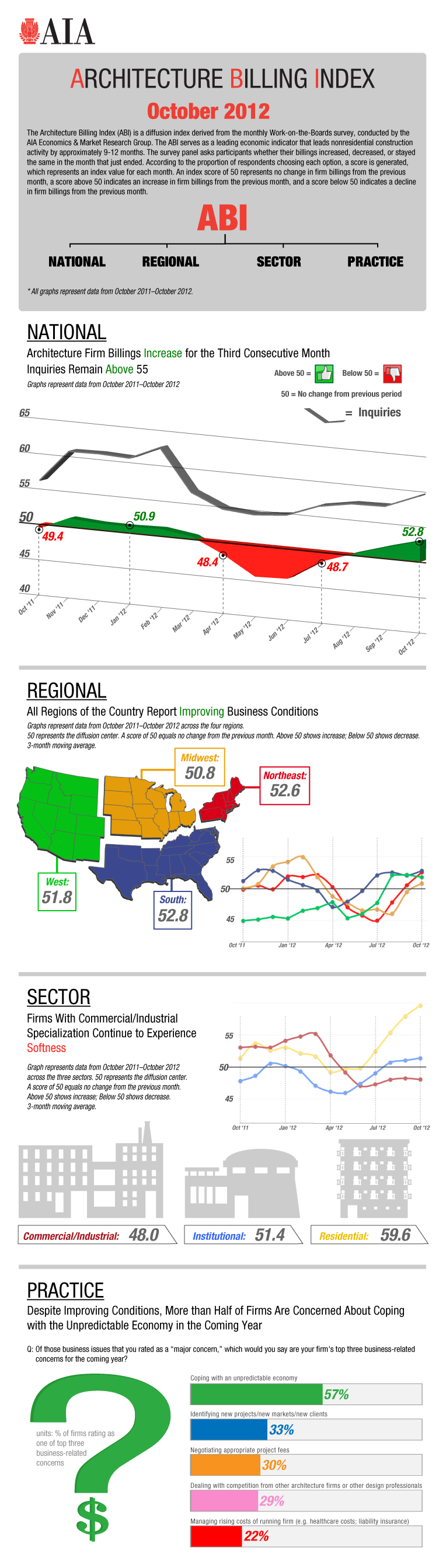

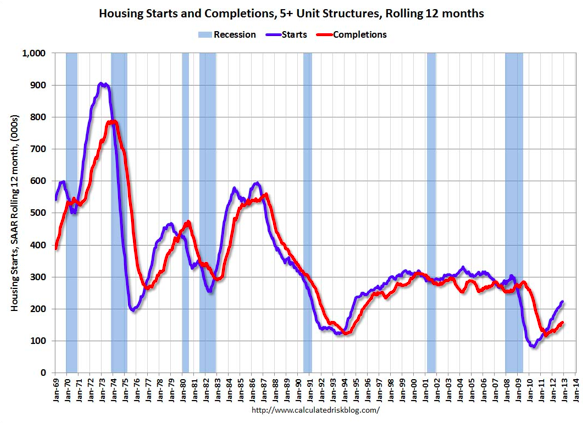

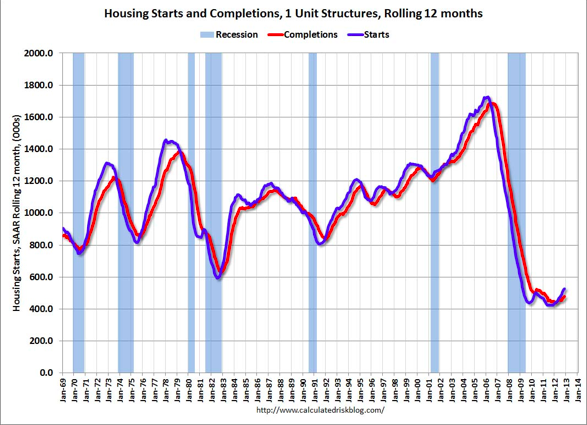

Just when I thought I was done for the year... A lot of news came out on the real estate and architectural markets, both of which are key leading indicators for the construction industry. Architectural Billings: AIA released its architectural billings index (ABI) for October today. ABI is considered a leading indicator for construction, typically leading construction activity by about a year (for more info, read this article). Here's the good news: The ABI composite was 53.2 in October, up from 52.8 in September (50 is the threshold between positive and negative billings). More good news: the ABI is above 50 across all regions in the United States. Even more good news: the ABI is above 50 in the institutional (think schools and hospitals) and residential (multi-family and high rise housing) markets. ABI for the institutional market is 51.4, up from 51.0 in September, while the ABI for the residential market is 59.6, up from 57.3 in September. But there is some bad news: the ABI for the commercial/industrial market is still below 50. Worse, it fell from 48.4 in September to 48.0 in October. Not a huge fall, but it still shows weakness. I wrote earlier today that the longer-term indicators that suggest the commercial real estate market is stabilizing and possibly getting better (note: this is my assessment of the commercial real estate market, not architectural billings or the construction industry). But in the near term, ABI is contracting for commercial/industrial projects, which means the construction industry surrounding the commercial/industrial market may still have some pain to experience. Below is the full take of AIA (full version can be found here and the press release can be found here):  As the bottom of the graphic shows (and I've mentioned plenty of times before), some of the weakness in the market is due to "uncertainty" in the economy. Corporations and large investment funds have tons of cash on the sidelines, but they won't invest it until they feel better. What will make them feel better is anyone's guess. Single Family Housing: I said earlier today that I wasn't as interested in single family housing because I'm more interested in projects that involve larger commercial general contractors. However, as previously mentioned, single family housing is a leading economic indicator for the U.S. economy in general (i.e. not just the construction industry). There was a lot of interesting data presented today. First the bad news (or maybe the not-as-good news). Mortgage applications decreased 12.3 percent from the previous week according to data collected by the Mortgage Bankers Association (see press release here). CoreLogic also tweeted that housing starts were down 3% in November (CoreLogic doesn't have any data backing that figure up on their webpage, but let's assume the tweet is correct). Taking both of these data points together (again, one I cannot fully substantiate), it shows that the housing market maybe showing some slight signs of weakness. Let me be clear: mortgage applications and housing starts are not the same thing. But housing starts and mortgage applications both are a function of demand. It could be that demand is slackening, at least in the recent past. The good news, however, is boffo good news. CoreLogic, in the same tweet (which again, the data behind it has not been substantiated) states that housing starts are up 27% year-to-date with strong growth in all regions with the exception of the Northeast. Bill McBride at the Calculated Risk blog states that housing starts are on pace to increase 25% in 2012 (I'm not sure where Mr. McBride got his data, but you can see his blog post here). Interesting, Bill goes on to point out that the 770,000 housing starts in 2012 will be the 4th lowest total since 1959, which is when the Census Bureau started collecting such data (the three lower years being those between 2009 and 2011). It shows we're emerging from a pretty big crater. Bill was full of interesting data today: The upper graph shows housing starts and completions for multi-family housing. There are two interesting takeaways from the data. First, the data is trending positively. Secondly (and this I'll admit I'm hoping my students will see) is that there is a one-year lag between starts and finishes. That's because it takes approximately one year to complete multi-family projects (obvious the size of the project/number of units also impacts the schedule).

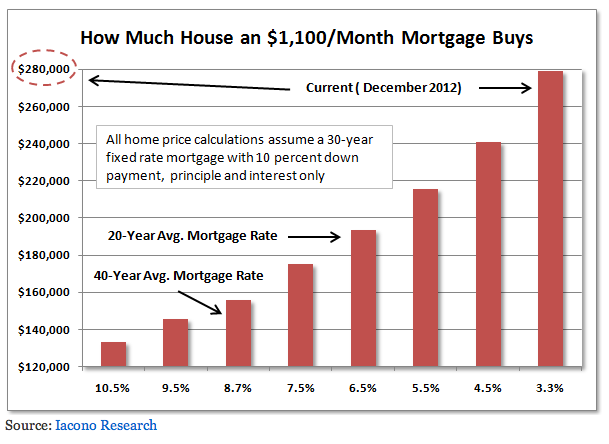

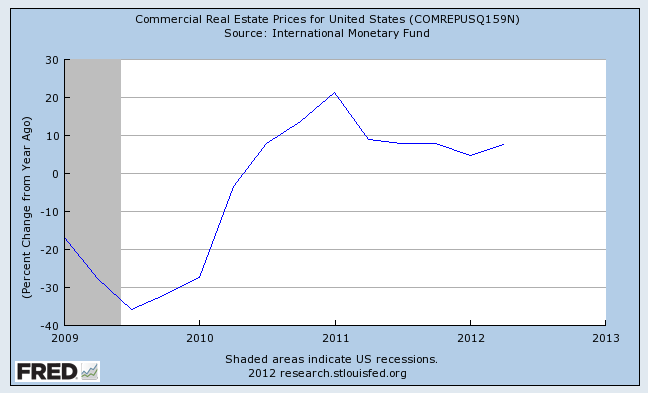

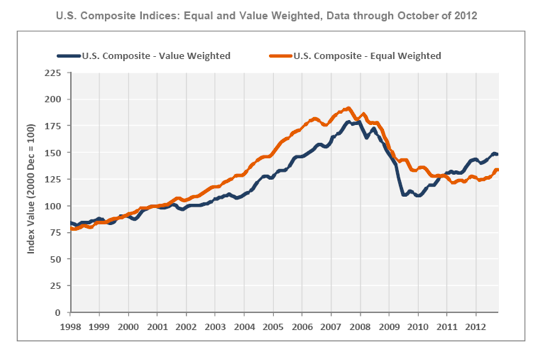

The second graph shows starts and completions for the single family housing market. It's also tending positively (albeit much more muted than multi-family). The lag between starts and finishes, however, is only six months which, not so coincidentally, is the approximate amount of time necessary to build a single family home. Bottom lines: 1) Architectural billings are up, and that's a good sign for the construction industry. There's still some weakness in the commercial/industrial market, but the other markets are positive and strengthening. 2) there is some recent signs of weakness in the single family housing market, but the last 12 months have been a home run. Hopefully these very recent trends are an anomaly, because as the housing market strengthens, confidence in the general economy increases. And that is also a good thing for the construction industry. I've been noodling on the real estate market for the past few months as I see it as a health indicator for the construction industry. As I have posted earlier, the housing market seems to heating up nicely. That's great for the economy as a whole, but I'm more interested in the types of construction projects that will get larger general contractors and their subcontractors working more. So how are those projects moving? Well, let's dig into that a little. Commercial Real Estate I am very curious about commercial real estate. I mean, if the housing market is moving in a positive direction, commercial building cannot be far behind it, right? The same low rates that are enticing people to buy houses are basically available to real estate developers as well. With borrowing rates low, you can build more space for the same loan size, as is represented in the figure below: I know, I know...the above is for home mortgages. But the same idea applies to borrowing for commercial real estate. Right now, you can build more space for the same loan payment, or so my thinking goes. But there in lies the rub. My thinking fails to grasp that there is still a glut of commercial space on the market. I spoke to two friends of mine in the commercial real estate market, and they say that development of new space will not increase until the level of vacancies decreases. Their take on this makes perfect sense, especially since we're in Sacramento which over-developed commercial space at a crazily drunken pace before the market crashed. Do the problems of Sacramento apply to the broader United States? Probably, but there are signs of life. Check out these graphs: The first of the three graphs shows data collected by the St. Louis Fed. Commercial real estate prices climbed rapidly until 2011 before steeply declining until end of Q1 2011. Since then, prices have been treading water, but they have ticked up positively in 2012 (this data only shows for Q1 2012, but even after taking the rose-colored glasses off, prices, at worst, have seemed to stabilize).

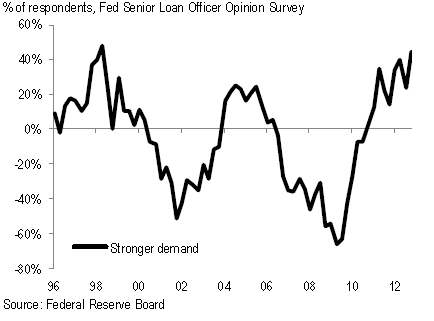

The second of the three charts (from the Calculated Risk Blog) shows the U.S. Composite Indices (last updated in October), which are two broad measures of aggregate pricing for commercial properties (you can find the whole article describing the indices here). It's subtle, but while prices decreased slightly in October, they are up quarter-over-quarter and year-over-year, and the Value-Weighted index is up 35% since bottoming out. I repeat, this is subtle, but the trends are positive. The last of the three graphs shows the results of a survey conducted with commercial real estate lenders by the Federal Reserve (see the chart and some analysis from Cullen Roche at the Pragmatic Capitalist blog). The demand for commercial real estate loans, which I would think would be a good indicator of projects to be developed, is trending positively. Lending activity is choppy over the past two years (probably due to general "market uncertainty"), but it is trending positively and is way off its low. So what does this mean? In the worst case scenario, commercial real estate prices are stabilizing, and in the best case scenario prices are increasing modestly. Lending activity is increasing. Taken together, I think this calls for cautious optimism for builders that commercial building will increase in the next year. Certainly, there will be pockets of strength (e.g. San Francisco/Oakland/San Jose Bay Area) and pockets of weakness (Central Valley of California, which interestingly enough, is not far from the Bay Area), but the general trends are slightly positive, generally speaking. Hopefully they stay that way or improve (duh, right?). Multi-Family/Mixed Use Development So the single family market is improving (due to declining inventory and low mortgage rates, among others), what about dense urban housing? I haven't collected any data (it's finals week and I'm swamped with grading), but I have collected four articles on large-scale projects in big North American cities. It seems that housing, while choppy, is always a good bet in big cities because the markets will rebound, particularly in the cities highlighted below: Washington D.C.: Developers are planning a 27-acre mixed use (1,300 residences, 960,000 SF or commercial space) in southwest D.C. (read more about it here and thanks to by friend Young Hoon Kwak for posting this link on Facebook). The developers are seeking $1.5 billion in financing, so it's not like they will be breaking ground tomorrow, but this is a good sign for commercial builders in D.C. Toronto: Toronto seems positively efforvescent in terms of high-rise construction, with 31 projects greater than 150 meters (almost 500 feet) slated to be completed by 2015. Check out the picture in this article. It looks like an Autobots vs. Decepticons battle featuring tower cranes. Hopefully this isn't the sign of a bubble...but it is a sign of commercial builders working! New York: More big building projects in the BK (that's Brooklyn for those of you unfamiliar with the rap game), this time with a 32-story residential tower on top of the newly-build Barclays Center (the house Jay-Z built and home of the Brooklyn Nets). This project is another piece of the massive Atlantic Yards redevelopment project. A cool feature regarding the construction of this project is that it will be completely pre-fabricated off-site and trucked into place. The general contractor is Skanska, and if you want to observe the future of the construction industry, watch this project. To read more about the project, check out this article. San Francisco: Last, but not least, check out what is being planned in SF. Lennar is planning on building over 20k housing units in the City's Hunter's Point, Candlestick and Treasure Island areas (all former U.S. Naval Bases and, I suspect, full of environmental hazards). What's unique about this project, besides the size and scope for an SF project? It is being funded by loans (to the tune of $1.7 billion) from China Development Bank and will be built by a Chinese general contractor, China Railway Construction Co. The project is expected to take 16 years to complete and will create an estimated 5,000 jobs. China has been investing in the U.S. government for years, but this combo of direct Chinese investments coupled with a Chinese builder is unprecedented. U.S. lenders and contractors should take note, as this project will likely be a signal of future trends (good or bad, depending on your perspective and the success/failure of the project). To read more, check out this article. So no scientific data, and certainly investments in those cities are, very relatively speaking, safe in any economic state due to the fact that they are major centers of commerce, so they cannot be used to draw broad conclusions. But they do show, anecdotally, that activity is picking up. When assessing technologies, I often look at them through the lens of increasing returns. Increasing returns are simply defined in this HBR article written by Brian Arthur (*side note: increasing returns, as promoted by Arthur, has faced a lot of scrutiny by economic scholars. I acknowledge this, but I still like the framework due to its simplicity for non-professional economists like myself). Increasing returns are bestowed upon products that get ahead in the market and get continuously further ahead and produce above normal profits. Products, particularly those in high tech markets, are able to produce increasing returns because they possess three characteristics:

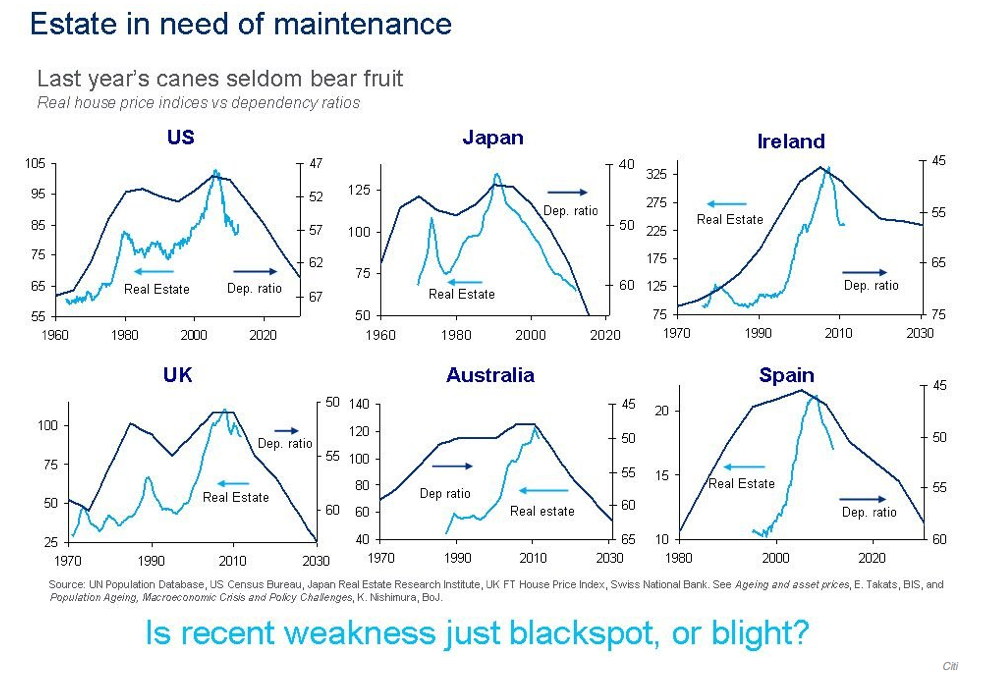

When a product has these three characteristics and become the dominant product, it is unlikely uses will readily switch once they have made the investment in the product. Arthur uses the example of operating systems. In the 1980s, there were multiple competing operating systems that had an opportunity to become the de facto standard: CP/M, DOS and Apple’s Macintosh. When Microsoft successfully licensed DOS and then negotiated with IBM to be the exclusive platform for their computers, that was the break they needed to become the industry standard. This happened despite the fact that DOS wasn’t the first to market or even the best product on the market. But we all know how the story ended: Microsoft became the industry leader and made tons of money, and became the standard for the industry, which meant more and more people kept buying it. Only until very recently has Microsoft’s dominance been challenged, and not until after most of the world invested heavily in Microsoft products. Since my focus is construction, let me give you an example of construction software: Primavera P3 (or more specifically, the current network-capable version, P6). P6 is a complicated program. I don’t know the development costs, but they were likely very high. Most sizeable contractors and agency CMs have a copy of it, so there is almost someone on a relatively large construction project that knows how to use it. It’s complicated to learn, but once someone knows how to use it, it becomes the standard for most contractors. It’s the standard scheduling software product in the industry. There’s just one problem: this whole model for increasing returns seems to be breaking down. Software is no longer that expensive to develop. Building on operating systems like Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android, a few programmers with access to a server, space in their parents’ basements, and some pizza and Mountain Dew can create apps that are powerful and easy to use (and venture capitalists are very happy with this capital efficient model for software development, which is why there is a robust seed-stage investing market for it). These apps and the operating systems are increasingly simple to use. Digitally adept Millennials and Gen Y’ers can pick up a device that runs either operating system and master apps on them very quickly. The reduction of development costs and the ease of users to switch almost seamlessly between operating systems and apps means it will be a long time before a dominant technology platform can have a virtual monopoly over users (but this is why Apple, Google and even still Microsoft are fighting like mad to get a strong foothold in this market with the long-term hopes of getting the same break Microsoft did in the 1980s). It’s not hard for most people to picture an app being developed that could credibly challenge status quo technologies (like Primavera P6). The only characteristic of increasing returns left that holds are the network effects, which can be better described by Metcalfe’s Law. Metcalfe’s Law states that the value of a communications network is proportional to the square of the number of users connected to the system. A particular technology becomes more valuable as the more users of that technology become connected. One mobile phone is essentially worthless because it has nothing to connect to. Two mobile phones have value as they allow two people to communicate from a distance. A network of thousands of mobile phones has a value of 1,000 squared if there is a person on the end of each phone willing to talk with the other phone users. As has happened in other industries, construction companies are beginning to enjoy the benefits of technology. As communication is fostered on projects due to the number of interconnected people using tools for which there is no dominant standard, are inexpensive to develop, easy to use, and companies are willing to pay for (or individuals are willing to pay for them because they are inexpensive and make their lives easier), a market for construction management tools should emerge (it’s early, but it looks like it’s happening). A complicating factor for construction companies will be the lack of a standard. If a standard operating system emerges, construction companies will arrange their IT investments around it. Until then, they must be prepared to manage devices that run different operating systems and be prepared to manage multiple operating factors. The bottom line: IT is becoming less expensive and easier to use, and the benefits of a well-connected team are becoming evident in the construction industry. As construction companies utilize technology more, and importantly, pay for the technology, a robust market for apps should emerge. The difficult part for builders is that because a dominant platform has not emerged, they will have to be prepared to manage more than one, complicating things somewhat. An analyst for Citgroup, Matt King, created what he proclaimed "the most depressing slide I've ever created" and presented it a few days ago: Real estate prices are straight forward (and they're for single family houses). The dependency ratio is the proportion of people that are working age to those that aren't or, in other words, the ratio of people that can reasonably be expected to be working to those that can't. As the proportion of the population that isn't working grows relative the proportion that is, which is currently happening in much of the developed world because of the aging workforce (birth rates are dropping, so the dependency ratio is not due to more babies being born), real estate prices drop and are expected to continue dropping (for a bunch of reasons, one of which being that as retirees downsize their housing needs and there are not as many younger buyers remaining to buy the house they're moving from, causing housing prices to drop).

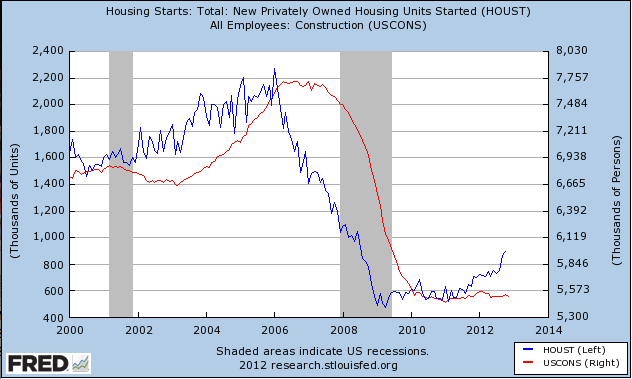

I get that it's a pretty simple slide that shows some trends, and I furthermore understand that correlation is not causation. As a home owner, it kind of scares me because most of my wealth is wrapped up in my house. But as a student of economics as it applies to the construction industry, I cannot help wondering what this slide means for the future of building homes. If the value of single family housing drops precipitously over the next decade or two, does that mean that single family homebuilding will also decrease on a relative basis? This is a big deal, as the largest segment of the construction industry is in the single family sector, and as goes single family housing, so goes the rest of the construction market. There may actually be a huge opportunity here, though. If you are a builder that specializes in multi-family housing, either apartments or high-rises, this could be great news. The population of the countries in the figure above, including the United States, isn't decreasing, it's just getting older. People will still need housing, just maybe not single family homes. The single family housing market is starting to heat back up, but that's due in large part to low mortgage rates, low supply and mass home buying by private equity investors (who will likely rent the homes, at least in the near term). Longer term, the cost of capital is going to go up (it can't get much lower and quantitative easing cannot go on forever). The conventional wisdom regarding home ownership as a solid investment is being challenged, notably by Nobel Prize winning economist Robert Shiller (see video here). And many people that would traditionally be the age of purchasing their first home are holding off on doing so (they're too busy paying off student loans). This doesn't inspire a great deal of long-term confidence in the single family housing market. But going back to what originally made me curious about this. If there is an opportunity for the developers and builders of multi-family housing projects, then that may spillover into other necessary construction projects. Like single family housing, multi-family housing will spur the construction of schools, retail space, hospitals, etc. But it may also spur big infrastructure investments, such as mass transportation projects. I'm guessing the face of housing will change dramatically over the next 20 years to the detriment to single family housing builders that fail to evolve, but that will create opportunities for other builders that are ready can respond to the change in the market. I have been reporting how the housing market is picking up steam. The housing market is important to commercial construction because when you build homes, other structures tend to follow (schools, retail, hospitals, offices, etc.). There's another reason why it's important to watch housing numbers: homebuilding is a leading indicator for overall construction employment. Take a look at the graph below: Hopefully this uptick in housing starts is signaling that overall construction employment is about to improve (construction was disproportionately hammered during the recession, although it was also a part of the problem). If employment rates improve, hopefully so will wages. This could be particularly good news for my students seeking jobs!

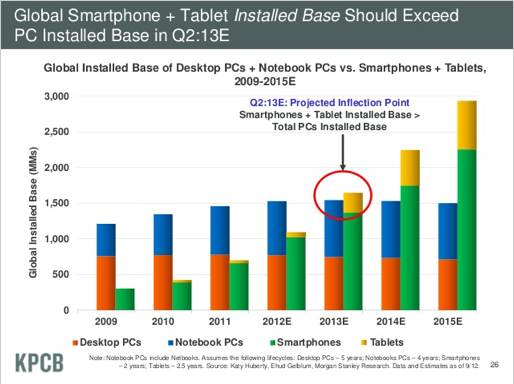

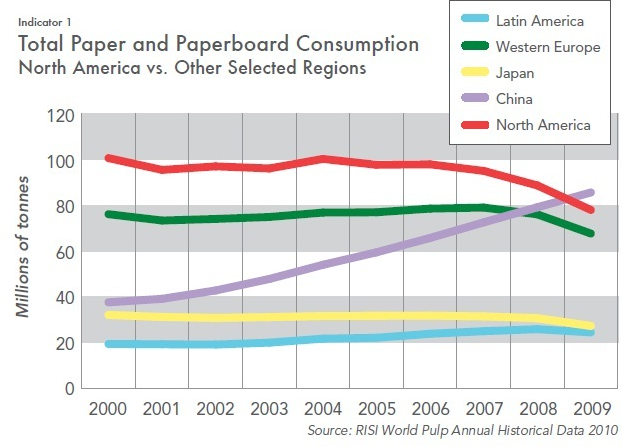

I'll show you two graphs that will provide two very obvious clues: The chart above is from the KPCB 2012 Internet Trends presentation (you can find the entire slide deck here). The entire presentation is full of interesting data, but I really like this slide. Look at how smart phones and tablets are growing relative to desktops and notebooks. However, that's only the first clue. Check out this next graph: I found the above figure on the Conversable Economist blog (see the whole post here).

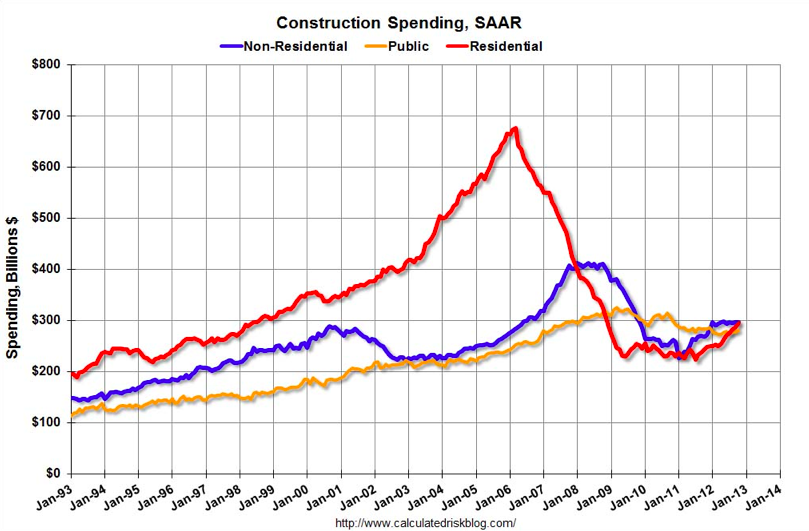

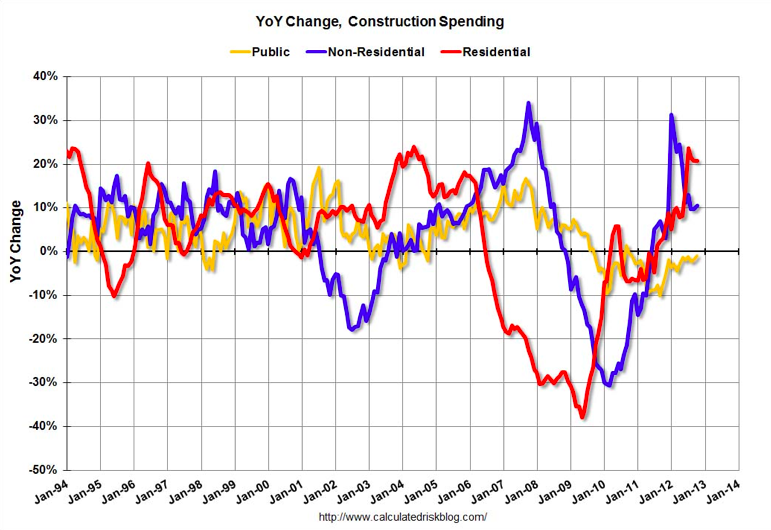

So how is construction, particularly documentation going to change? It's going electronic. Is your company ready for this sea change? Today is a big day on the construction economics front. For a deep dive, go to Bill McBride's Calculated Risk blog. A few graphs on the site tell a good story: First, we (and by we I mean the construction industry) are still WAY off our past highs (as if anyone needs me to restate the obvious). But the trends have been getting better (much better if you go back to the lows). Most of the recent gains have been in the single-family housing construction market, a continuation of a trend that has been described by me in the past and by Bill McBride today. The commercial, industrial, and infrastructure markets are still a bit weak. Looking at year-on-year data, the strength in the residential market is even more pronounced. However, there are signs of strengthening in the public market (projects sponsored by local, state, and federal government agencies). Baby steps for sure, but every little bit helps. The non-residential (read: commercial) market has seemingly fallen off a cliff after some really nice gains from 2010 to early 2012. As I have written in the recent past, this seems to be due to uncertainty in the business community. I'm sure all of this fiscal cliff stuff is not helping that...

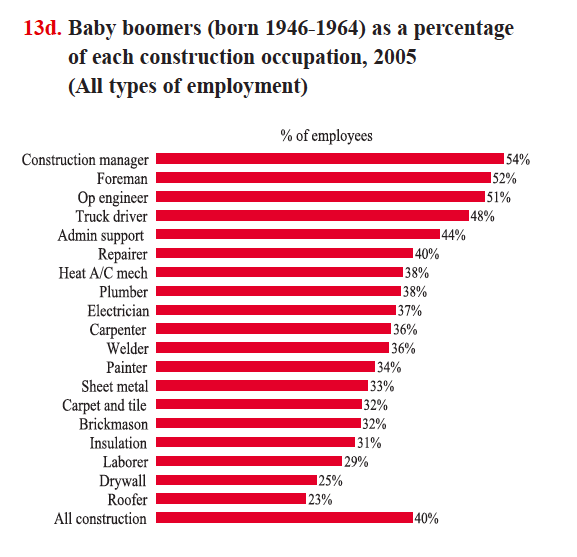

The bottom line: spending on construction is growing and we're way off the industry lows of 2009 and 2010. Most of that growth is in single-family housing, which is the largest portion of the U.S. construction industry. This doesn't help the larger commercial contractors and their subcontractors I regularly talk to (the ones that hire my students and support my department!), but hopefully optimism in the housing sector will create some optimism in the rest of the industry. In Part 1, I wrote about how low the IT spend in the construction industry is. The lack of spending on IT means that builders are missing out on a major source of productivity gains. I also mentioned in Part 1 that low profitability in the construction industry, relatively speaking, means that there's not a lot of capital sloshing around on the balance sheets of construction companies to be invested in IT. That's a major problem. A second major problem will be discussed below in Part 2. So, construction companies spend lightly on IT. That isn't the only reason why the industry is missing out on productivity gains afforded by IT investments. Another big reason is that many people in the construction industry are, uhhh, how do I put this...old. When I talk to people in industry (particularly those managing specialty subcontractors), they commonly tell me that they have become very serious about hiring young college grads because they need new blood to replace the baby boomers, who tend to dominate management in the construction management. That anecdotal evidence is supported in the chart below: The chart above was created from data compiled by the Bureau of Labor and reported by The Center for Construction Research and Training. The full report can be downloaded here. The data is from 2005, but it confirms what people are saying today: the construction industry is graying. And notice where the baby boomers in the construction industry are concentrated: as construction management (and I don't know who is included in the construction manager category, but I suspect it includes project managers, superintendents, project executives, etc.) and foremen. The people running projects and craft labor tend to be older. This should shock no one for two reasons. First, in most cases, it takes time and experience to get promoted to management. Secondly, most people who perform craft labor tend not to work in craft labor too late in their lives because it's, by and large, hard work. Many baby boomers have left the craft labor ranks.

So now that I've insulted baby boomers in the construction industry as being less productive, what does age have to do with IT adoption? Well, a lot. Technology adoption is more difficult in a population that did not grow up with personal IT devices, whereas younger people, who are considered digital native (which is just a fancy way of saying they grew up with personal computers, mobile phones, and gaming devices) take to IT with great ease. So the majority of the people managing construction projects and companies come from a generation that tends to adopt technology only as they feel pressured to do so. If you think these are stereotypes, check out this article. If I expected this trend to continue, it would be pretty dumb of me to be calling for a technological revolution in construction, right? As previously mentioned, there is a changing of the guard in the construction industry, whereby the baby boomers are retiring in droves and the Gen Ys and Millennials replacing them are bringing their technology with them. And it's not an orderly transition, at least as IT is concerned. In the past, construction companies had to make big bets on technology adoption (buying desktop PCs and later laptops, investing in Windows and the Office suite of programs, and other expensive software (back-end databases, Primavera P3, AutoCad, etc.). It took training and effort for these IT tools to be adopted, an effort many are reluctant to repeat. Fast forward to today, and many recent graduates of construction management, engineering, and architecture programs are entering the workforce and they think these older tools suck. Well, that may be a bit strong, but they have found stuff that works better in some cases, and they're bringing it onto job sites. I never really clicked with me until I saw this video a few days ago. I am a big fan of Paul Kedrosky's commentary on technology, and in this video he's talking about the convergence of technology and medicine, but at the one-minute mark in the video, he describes how iPhones became a business device (paraphrasing): people are tired of working with crap so they smuggle in their own better personal technology to work. And as discussed in a previous post, it's not just iPhones, it's iPads and other tablets. And it's not just the iOS, it's Android (leaving Windows wheezing in the distance). And it's not Window's based software, it's apps. A deluge of technology is finding it's way onto the job site, and that's a good thing. The hard part is "institutionalizing" it so that some form of a technology "platform" can be created and managed and not hacked together by individuals arbitrarily adding IT to the project. The bottom line: the demographics of the construction industry are changing, bringing in a new wave of younger technology-adept project management personnel, and they're bringing their technology with them. The next step: software developers will recognize this changing demographic as an untapped market and will increasingly develop new IT tools for the construction industry. That will create the disruption that Kedrosky talks about later in the aforementioned video, where he talks about how the medical industry needs to be disrupted because its technology adoption has lagged other sectors of the economy while its costs soar. Sound familiar? |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed