|

When assessing technologies, I often look at them through the lens of increasing returns. Increasing returns are simply defined in this HBR article written by Brian Arthur (*side note: increasing returns, as promoted by Arthur, has faced a lot of scrutiny by economic scholars. I acknowledge this, but I still like the framework due to its simplicity for non-professional economists like myself). Increasing returns are bestowed upon products that get ahead in the market and get continuously further ahead and produce above normal profits. Products, particularly those in high tech markets, are able to produce increasing returns because they possess three characteristics:

When a product has these three characteristics and become the dominant product, it is unlikely uses will readily switch once they have made the investment in the product. Arthur uses the example of operating systems. In the 1980s, there were multiple competing operating systems that had an opportunity to become the de facto standard: CP/M, DOS and Apple’s Macintosh. When Microsoft successfully licensed DOS and then negotiated with IBM to be the exclusive platform for their computers, that was the break they needed to become the industry standard. This happened despite the fact that DOS wasn’t the first to market or even the best product on the market. But we all know how the story ended: Microsoft became the industry leader and made tons of money, and became the standard for the industry, which meant more and more people kept buying it. Only until very recently has Microsoft’s dominance been challenged, and not until after most of the world invested heavily in Microsoft products. Since my focus is construction, let me give you an example of construction software: Primavera P3 (or more specifically, the current network-capable version, P6). P6 is a complicated program. I don’t know the development costs, but they were likely very high. Most sizeable contractors and agency CMs have a copy of it, so there is almost someone on a relatively large construction project that knows how to use it. It’s complicated to learn, but once someone knows how to use it, it becomes the standard for most contractors. It’s the standard scheduling software product in the industry. There’s just one problem: this whole model for increasing returns seems to be breaking down. Software is no longer that expensive to develop. Building on operating systems like Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android, a few programmers with access to a server, space in their parents’ basements, and some pizza and Mountain Dew can create apps that are powerful and easy to use (and venture capitalists are very happy with this capital efficient model for software development, which is why there is a robust seed-stage investing market for it). These apps and the operating systems are increasingly simple to use. Digitally adept Millennials and Gen Y’ers can pick up a device that runs either operating system and master apps on them very quickly. The reduction of development costs and the ease of users to switch almost seamlessly between operating systems and apps means it will be a long time before a dominant technology platform can have a virtual monopoly over users (but this is why Apple, Google and even still Microsoft are fighting like mad to get a strong foothold in this market with the long-term hopes of getting the same break Microsoft did in the 1980s). It’s not hard for most people to picture an app being developed that could credibly challenge status quo technologies (like Primavera P6). The only characteristic of increasing returns left that holds are the network effects, which can be better described by Metcalfe’s Law. Metcalfe’s Law states that the value of a communications network is proportional to the square of the number of users connected to the system. A particular technology becomes more valuable as the more users of that technology become connected. One mobile phone is essentially worthless because it has nothing to connect to. Two mobile phones have value as they allow two people to communicate from a distance. A network of thousands of mobile phones has a value of 1,000 squared if there is a person on the end of each phone willing to talk with the other phone users. As has happened in other industries, construction companies are beginning to enjoy the benefits of technology. As communication is fostered on projects due to the number of interconnected people using tools for which there is no dominant standard, are inexpensive to develop, easy to use, and companies are willing to pay for (or individuals are willing to pay for them because they are inexpensive and make their lives easier), a market for construction management tools should emerge (it’s early, but it looks like it’s happening). A complicating factor for construction companies will be the lack of a standard. If a standard operating system emerges, construction companies will arrange their IT investments around it. Until then, they must be prepared to manage devices that run different operating systems and be prepared to manage multiple operating factors. The bottom line: IT is becoming less expensive and easier to use, and the benefits of a well-connected team are becoming evident in the construction industry. As construction companies utilize technology more, and importantly, pay for the technology, a robust market for apps should emerge. The difficult part for builders is that because a dominant platform has not emerged, they will have to be prepared to manage more than one, complicating things somewhat.

0 Comments

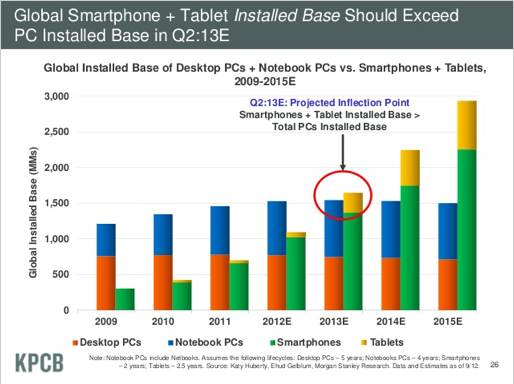

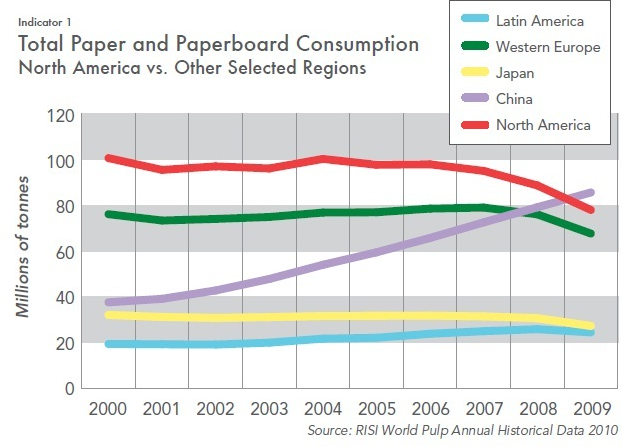

I'll show you two graphs that will provide two very obvious clues: The chart above is from the KPCB 2012 Internet Trends presentation (you can find the entire slide deck here). The entire presentation is full of interesting data, but I really like this slide. Look at how smart phones and tablets are growing relative to desktops and notebooks. However, that's only the first clue. Check out this next graph: I found the above figure on the Conversable Economist blog (see the whole post here).

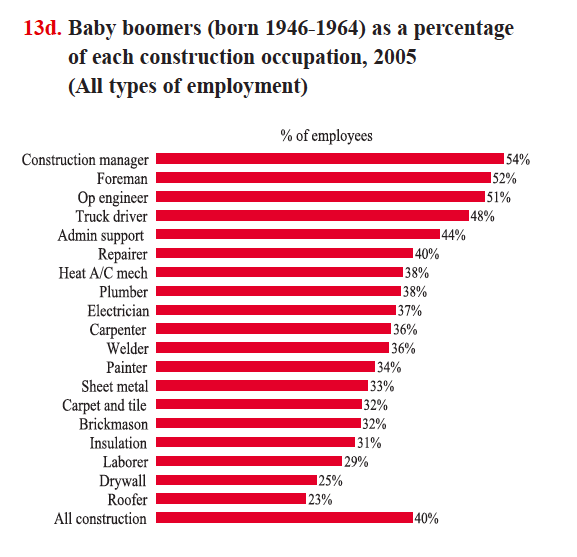

So how is construction, particularly documentation going to change? It's going electronic. Is your company ready for this sea change? In Part 1, I wrote about how low the IT spend in the construction industry is. The lack of spending on IT means that builders are missing out on a major source of productivity gains. I also mentioned in Part 1 that low profitability in the construction industry, relatively speaking, means that there's not a lot of capital sloshing around on the balance sheets of construction companies to be invested in IT. That's a major problem. A second major problem will be discussed below in Part 2. So, construction companies spend lightly on IT. That isn't the only reason why the industry is missing out on productivity gains afforded by IT investments. Another big reason is that many people in the construction industry are, uhhh, how do I put this...old. When I talk to people in industry (particularly those managing specialty subcontractors), they commonly tell me that they have become very serious about hiring young college grads because they need new blood to replace the baby boomers, who tend to dominate management in the construction management. That anecdotal evidence is supported in the chart below: The chart above was created from data compiled by the Bureau of Labor and reported by The Center for Construction Research and Training. The full report can be downloaded here. The data is from 2005, but it confirms what people are saying today: the construction industry is graying. And notice where the baby boomers in the construction industry are concentrated: as construction management (and I don't know who is included in the construction manager category, but I suspect it includes project managers, superintendents, project executives, etc.) and foremen. The people running projects and craft labor tend to be older. This should shock no one for two reasons. First, in most cases, it takes time and experience to get promoted to management. Secondly, most people who perform craft labor tend not to work in craft labor too late in their lives because it's, by and large, hard work. Many baby boomers have left the craft labor ranks.

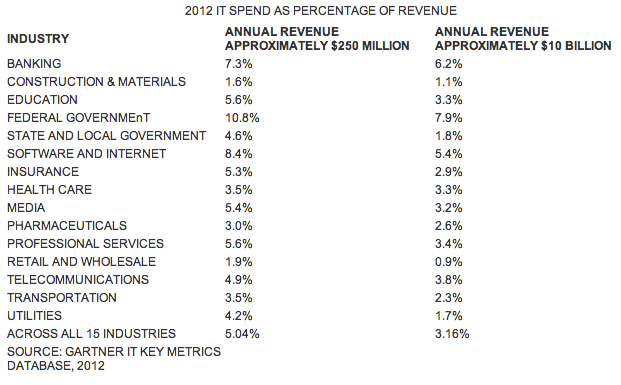

So now that I've insulted baby boomers in the construction industry as being less productive, what does age have to do with IT adoption? Well, a lot. Technology adoption is more difficult in a population that did not grow up with personal IT devices, whereas younger people, who are considered digital native (which is just a fancy way of saying they grew up with personal computers, mobile phones, and gaming devices) take to IT with great ease. So the majority of the people managing construction projects and companies come from a generation that tends to adopt technology only as they feel pressured to do so. If you think these are stereotypes, check out this article. If I expected this trend to continue, it would be pretty dumb of me to be calling for a technological revolution in construction, right? As previously mentioned, there is a changing of the guard in the construction industry, whereby the baby boomers are retiring in droves and the Gen Ys and Millennials replacing them are bringing their technology with them. And it's not an orderly transition, at least as IT is concerned. In the past, construction companies had to make big bets on technology adoption (buying desktop PCs and later laptops, investing in Windows and the Office suite of programs, and other expensive software (back-end databases, Primavera P3, AutoCad, etc.). It took training and effort for these IT tools to be adopted, an effort many are reluctant to repeat. Fast forward to today, and many recent graduates of construction management, engineering, and architecture programs are entering the workforce and they think these older tools suck. Well, that may be a bit strong, but they have found stuff that works better in some cases, and they're bringing it onto job sites. I never really clicked with me until I saw this video a few days ago. I am a big fan of Paul Kedrosky's commentary on technology, and in this video he's talking about the convergence of technology and medicine, but at the one-minute mark in the video, he describes how iPhones became a business device (paraphrasing): people are tired of working with crap so they smuggle in their own better personal technology to work. And as discussed in a previous post, it's not just iPhones, it's iPads and other tablets. And it's not just the iOS, it's Android (leaving Windows wheezing in the distance). And it's not Window's based software, it's apps. A deluge of technology is finding it's way onto the job site, and that's a good thing. The hard part is "institutionalizing" it so that some form of a technology "platform" can be created and managed and not hacked together by individuals arbitrarily adding IT to the project. The bottom line: the demographics of the construction industry are changing, bringing in a new wave of younger technology-adept project management personnel, and they're bringing their technology with them. The next step: software developers will recognize this changing demographic as an untapped market and will increasingly develop new IT tools for the construction industry. That will create the disruption that Kedrosky talks about later in the aforementioned video, where he talks about how the medical industry needs to be disrupted because its technology adoption has lagged other sectors of the economy while its costs soar. Sound familiar? A running theme of this blog (and of my research and personal interests) is that the construction industry is going to see a dramatic and positive change in how it adopts technology. I've been mulling this over for two days now and am going to write about some of my thoughts on this subject in three parts, with this being the first (I should be grading assignments and exams, but I always find it more interesting to write, or even clean my rain gutters, when grading is the alternative...). The construction industry spends an incredibly low amount of money on IT. The lowest among many industries integral to our country's economy: The data in the figure above was compiled by Gartner and was reported by ENR and can be found here. The ENR article reiterates the oft-used Bureau of Labor stat that 70% of productivity gains come from IT. So there's a huge opportunity being lost to improve productivity, which means there's a huge opportunity to be gained.

*Side note 1: Just because the construction industry is losing out on productivity gains based on IT investments, it is making efforts to improve productivity. As my friend Thaís da C. L. Alves pointed out to me, the construction industry is making productivity gains in off-site fabrication, as discussed in this paper (which I haven't yet read in its entirety). *Side note 2: I understand that the construction industry cannot just wave a magic wand and increase IT spending to 5% of revenues without there being ramifications, good and bad. Construction is a competitive business with low gross margins. Low technology spending, given the low overall relative profitability of the industry, is to be expected. Side note 2 notwithstanding, I will be writing follow-up posts as to why the construction industry has been slow to adopt new productivity-enhancing IT tools and how that's going to change in the not-so-distant future. Also, the data above represents IT spending across the industry. Some companies have increased their IT spending with very positive results. However, the bottom line is that currently, the construction industry spends way less than other industries on IT and is not capitalizing on productivity gains enabled by IT. |

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed